Team

Multimessenger Astrophysics

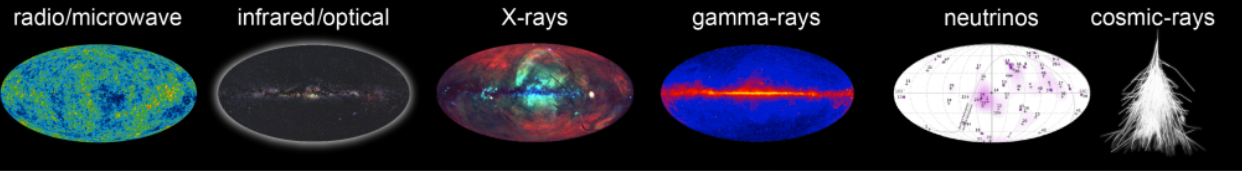

Since the dawn of humanity the cosmos has been studied using visible light; first with the naked eye, and since the early 17th century increasingly with optical telescopes. Telescopes then played a key role in establishing the heliocentric worldview, and allowed a first glimpse at the magnificence and richness of objects in the Universe. In the late 19th century, Maxwell's equations predicted that there is even more than what meets the eye. Driven by a myriad of technological innovations, the 20th century saw the opening of the entire electromagnetic spectrum to study the Universe, from radio waves to gamma-rays. This enabled us to study in great detail many aspects of the Universe, including the early hot phase just after the Big Bang, the formation of galaxies and stars, and extreme objects like neutron stars and black holes.

Caption: The sky at different frequencies (first 4 panels) and neutrino and charged cosmic rays. Source: Planck, ROSAT, Fermi, IceCube

Nowadays, yet another phase in studying the Universe has arrived, with the addition of all kinds of other non-light signals: Highly energetic particles (cosmic rays, discovered in 1912), and the very hard to detect neutrinos (first detection of solar neutrinos in 1968) and gravitational waves. Gravitational waves are the latest addition to these cosmic harbingers, predicted by Einstein already in 1916, and first detected only in 2015. All these different signals provide us with highly specific knowledge about the physical processes that take place in the Universe. The study of objects like black holes, of neutron stars and star forming regions, or explosive/transient events in the Universe, using the full range of these signals, is referred to as “multi-messenger astrophysics”.

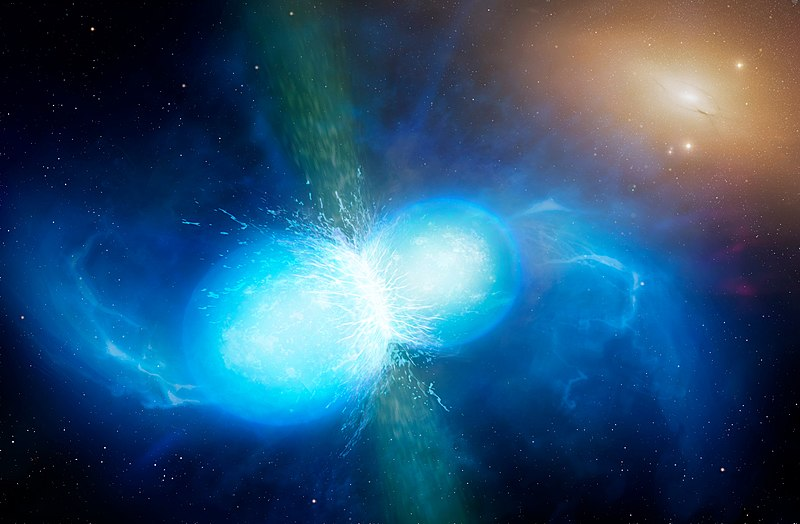

Many of these messengers may act at the same time. For example: if two neutron stars spiralling around each other finally merge into a new object, probably a black hole, the in-spiralling leads to the release of gravitational waves, which can be detected. The merging of the two neutron stars itself leads to a powerful nuclear explosion producing much light, but the final compact object also launches jets that give rise to the acceleration of particles such as protons and electrons to very high energies. The energetic electrons will radiate across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, whereas the protons could contribute to the cosmic rays detected on Earth, or they may collide in the neighbourhood of the explosion with other protons and produce highly energetic neutrinos and gamma-rays.

Caption: Artist impression of a neutron star merger. Source: University of Warwick/Mark Garlick

Members of GRAPPA play a world-wide leading role in many aspects of multi-messenger astrophysics. The group of Christoph Weniger studies the generation and propagation of cosmic rays in the Milky Way using gamma-ray data.